This text was written as an assignment for the course The problem of meaning, part of the master's in Philosophy for Contemporary Challenges at the Open University of Catalonia. The original was written in catalan and can be read here.

The meaning of our time

Stars live maintaining a delicate balance of forces. Their gravity, generated by their mass, is a force that strives to compress and collapse the star. However, at the star's core, nuclear fusion reactions unleash immense energy, counteracting the force of gravity. Sometimes, this balance is disrupted —fuel is depleted at the core— and the star collapses, since there is nothing to stop the force of gravity. When another fuel begins to burn, the star enters another stage of its evolution until that too is exhausted. At the end of the star's life, if it is massive enough, nothing can stop the collapse: there are no new fuels to burn. The star implodes, and all the mass concentrates at a point of infinite density: the singularity, turning into a black hole.

If we were to observe the black hole from a distance, floating in spacetime, we would not see the singularity. It is protected by what is called the event horizon: an invisible boundary that imprisons everything. Nothing escapes it. We would literally see a black hole. From our perspective, everything falling into it would appear almost frozen in time, falling infinitely and indefinitely.

Beyond the event horizon, spacetime loses all familiarity. The singularity is no longer a point in space; it is a point in the future, from which no one can escape.

Our present is inscribed in the liminal spacetime that constitutes the event horizon. We observe our inexorable fall1 toward the singularity. We observe it like someone floating in spacetime; we know we have already crossed the horizon but find ourselves frozen on the border: timeless, ahistorical.

The event horizon as the liminal spacetime of the present

Our present is marked by two temporal scales. The temporal scale of neoliberal capitalism is that of immediacy: we can obtain whatever we want almost immediately with a click. Information, services, material objects, entertainment… we live immersed in an instantaneous temporality that stimulates, saturates, exhausts, and overwhelms us. This temporal scale leaves no space for reflection or digestion of what we are experiencing. As Daniel Inclán says (MACBA Barcelona Oficial, 2019), every day new information paralyzes or surprises us, which we don't finish processing because new information appears: our connection with today is a sum of instants.

Living in the present of immediacy distracts us and imbues us with a tale of progress, scientific and technological advances, globalization, free choice, and emancipation. It makes us think that individual autonomy and the satisfaction of desires are the great successes of a neoliberal capitalist society. We still inhabit the echoes of the postmodern narrative.

However, the narrative of progress coexists with the narrative of catastrophe: climate change, the loss of biodiversity, the instrumentalization of reason, the repression, the massacres, the precariousness, the exploitation, and an increasingly pathological society. The unsustainability of indefinite growth on a planet with finite resources is more evident than ever, and the consequences of human action are inevitable: consequences on a planetary scale and on the order of 100,000 years. Humanity has become a geological force. We have entered the Anthropocene.

The narrative of catastrophe tells us that the crisis has environmental, economic, social, energetical, geopolitical, and technological dimensions, and that it is already inevitable. If I may stretch the analogy a bit further, the star of human civilization literally has no more fuel to burn: the future is the collapse, under its own weight, of humanity as we know it.

Thus, the present is the transit —the liminal space(time)— toward collapse. Think of the liminal spaces we occupy in everyday life: elevators, buses, airports… We occupy these spaces with a waiting attitude, filling the wait with all kinds of distractions. Is this not also how we are living the present?

The inexorable fall toward the singularity

Marina Garcés writes in Nova Il·lustració Radical that ours is a posthumous condition because we inhabit after death, as the irreversibility of our civilizational death belongs to an experience of 'it already happened' (Garcés Mascareñas, 2017).

The posthumous condition is that of an existence beyond the event horizon. Crossing the horizon is a death sentence because the singularity is the inevitable future of everything that has crossed it. We have not yet reached the collapse, but it is already unavoidable. Effectively, we have already died.

Just as physics cannot say anything about what happens inside a black hole, it cannot tell us what the future holds. We have probabilities, estimates, margins, but physics still does not have a model that accurately describes the climate because there is still much to learn about chaotic systems. So, we face a big question.

Transforming the observation of the fall into thinking

Faced with the realization of the fall, we are overwhelmed by impotence. Our lives no longer depend on ourselves: we are a geological force as a collective, not as individuals, and individual action seems futile. This leaves us as we would appear if we looked at the black hole from outside: paralyzed.

Daniel Inclán says that the inhabitants of the 21st century suffer from historical orphanhood: we are people without historical attributes, without commitments to time or to the existences that were before us (MACBA Barcelona Oficial, 2019). The characteristical ahistoricity of our present, the forgetting of the past, is also the avoidance of the future. We prefer to float on the threshold than to face the collapse.

Therefore, the present is fragmented: two seemingly irreconcilable narratives coexist, and the temporal scales produce alienated individual experiences. Perhaps, then, the meaning of the present is to gather the fragments, learn to think them. The immediacy of our present demands instant-instinctive reactions, and reductionism and simplification are the tools we use to survive the pace of immediacy. A new thought is needed that surpasses this tendency and can reintegrate fragmented reality.

Marina Garcès says that the meaning of our posthumous condition is not in the threatening future they paint for us; it is in a past that is still our present, a present that we have not yet overcome (CCCB, 2016). Following Hannah Arendt's line of thought, digesting this past, understanding it, must produce a reconciliation with the world. As Adorno would say, the concept must make an effort to heal the wounds that the concept itself necessarily inflicts (Adorno, 1976).

Perhaps the meaning of the present is to understand death, to transit this death, without losing sight that in the transit there is also life. If I stretch the analogy a bit further: there might exist a 'beyond the singularity'; crossing a black hole might mean landing in a new world. As Daniel Inclán says, "Hay que cuidar la ruina, porque de la ruina saldrán los otros mundos posibles." (MACBA Barcelona Oficial, 2019)

Thinking, always, must be accompanied by action, as Brigitte Vasallo puts it: a thought that does not act is sterile, and an action that does not think is ephemeral. (CCCB, 2016)

It is necessary to transform the mythology surrounding the narrative of the catastrophe into something that allows us to work: "We need, not only a true state of the art —or better, a systemic analysis— of the economic and biophysical situation of the planet, but above all a comprehensive vision of what a collapse could be, how it could be triggered, and its psychological, sociological, and political implications for present generations. A genuine applied and interdisciplinary science on collapse is needed." (Servigne et al., 2021)

The relationship between the subject, history, and the sense of freedom in the face of the effects of our historical action, as a species, on the planet and its future

The Western tradition is accustomed to thinking in dichotomies. As Hannah Arendt writes in The Concept of History, Ancient and Modern (Arendt, n.d.), history has so far been understood as human action on a static background represented by nature, which was the cyclical and immutable that acted as a backdrop. The dichotomy is in the distinction between the mortal and the immortal, also between the human and the natural. It is a self-imposed, constructed difference that is now violently broken. The imaginary separation between the human and the natural is fading: humanity also initiates natural processes. (Arendt, n.d.) Grasping this reality is a challenge:

"To call ourselves geological agents is to attribute to us a force on the same scale as that released at other times when there has been a mass extinction of species.” (Chakrabarty, 2009)

This realization breaks the tradition, or as Svetlana Aleksievich writes:

"The individual has entered into a dispute with the previous representations of himself and the world. When we speak of the past and of the future, we introduce into these words our conception of time but, more than anything else, Chernobyl is a catastrophe of time." (Aleksievich, 2016)

The categories of thought from the past are no longer useful to us, they don't allow us to digest names like Auschwitz or Chernobyl. Thus, history must evolve into something that encompasses a broader subject and renounces differences and dichotomies as a foundation.

Similarly, the sense of freedom is called into question. Chakrabarty argues that giving freedom involves giving energy and therefore, the history of global warming adds a question mark in the history of freedom (CCCB, 2015), since modern freedom rises on the always expanding use of fossil fuels. (Chakrabarty, 2009)

In his second thesis, Chakrabarty writes: "Freedom has, of course, meant different things at different times, ranging from ideas of human and citizens’ rights to those of decolonization and self-rule. Freedom, one could say, is a blanket category for diverse imaginations of human autonomy and sovereignty." (Chakrabarty, 2009)

Is the current concept of freedom conceived during the Enlightenment really inherently linked to collapse, or are there more subtleties and complexities involved? "Under the rule of a repressive totality, freedom can become a powerful instrument of domination" (Marcuse, 1999), wrote Marcuse, and "The entirely enlightened earth radiates under the sign of a triumphant calamity" (Horkheimer et al., 2006), wrote Adorno and Horkheimer.

Is it possible to conceive of a freedom that does not result in an assault on existence?

One thing is clear: "whatever our socioeconomic and technological choices, whatever the rights we wish to celebrate as our freedom, we cannot afford to destabilize conditions (such as the temperature zone in which the planet exists) that work like boundary parameters of human existence." (Chakrabarty, 2009)

Who is we?

It's not easy to answer this question. While the crisis affects us as a species collectively —though it also affects us differently, as capitalism produces unequal geographies (MACBA Barcelona Oficial, 2019)— the responsibility for the historical action that triggered it belongs to the West, the capitalist economic system, and the modes of domination that characterize it.

"All the anthropogenic factors contributing to global warming—the burning of fossil fuel, industrialization of animal stock2, the clearing of tropical and other forests, and so on—are after all part of a larger story: the unfolding of capitalism in the West and the imperial or quasi-imperial domination by the West of the rest of the world." (Chakrabarty, 2009)

It is imperative that if we think of ourselves as a species, we do not erase the responsibility or the need for intra-species reparations.

Dipesh Chakrabarty argues that humans cannot have species experiences because there is no phenomenology associated with the species, and concepts can never be experienced (Chakrabarty, 2009). I disagree.

On the one hand, I consider that every category is a concept, and experiences are framed within the concept when intellectually reviewed. I can frame some of my experiences as an individual within the phenomenology of being a woman, only if the concept of woman exists in my society and I have intellectually apprehended it. On the other hand, these categories and concepts are often created in the face of otherness. If a human being lives permanently alienated from nature and other species, perhaps they will not be able to conceive of an "us" as a species, if they face instead the plurality and diversity of human experience.

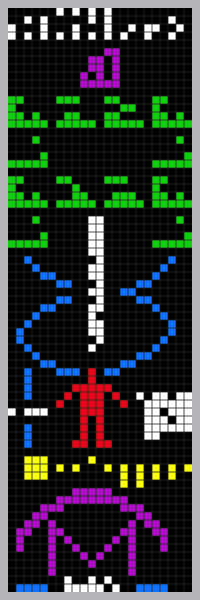

Thinking of ourselves as a species reminded me of the Arecibo message, shown in figure 1. A group of astronomers and astrophysicists designed a sequence of bits that were transmitted by radio into space with the aim of explaining the human species to an extraterrestrial otherness. They chose to communicate the atomic numbers of the elements that make up our DNA, the nucleotides of the double helix, the average height, and planet Earth as the location within the Solar System.

However, I believe that thinking of ourselves as a species still poses a separation from the non-human. Conceiving of an "us" limited to the species carries the risk of falling back into legitimizations of the exploitation of our planetary companions, non-human animals. And if we have learned anything, it is that systems of oppression reproduce and are interconnected. The spark of domination creates a fire that rages and spreads throughout all realms of existence.

If we continue to think that animals only exist as members of their species and not as individuals (Arendt, n.d.) —a conviction, unfortunately, prevailing in the current discourses— we will feed the belief that there are beings that do not deserve moral consideration. It is a belief that leads to dehumanizing fellow intra-species beings —leads to animalizing them!— and justifying modes of domination. As long as the animal is animalized in the way it is today, the human will also be animalized.

Therefore, I propose an "us" that is not limited to the human species. That does not fragment existences. That encompasses all those affected by the historical action of Western domination: a planetary "us", belonging to the biosphere. This undoubtedly has a specific phenomenology that we can experience. In this sense, we have much to learn from indigenous peoples who still preserve worldviews of the human species as part of a living whole.

Jason Hickel explains this in Less is more:

"This is the thing about ecology: everything is interconnected. It’s difficult for us to grasp how this works, because we’re used to thinking of the world in terms of individual parts rather than complex wholes. In fact, that’s even how we’ve been taught to think of ourselves – as individuals. We’ve forgotten how to pay attention to the relationships between things. Insects necessary for pollination; birds that control crop pests, grubs and worms essential to soil fertility; mangroves that purify water; the corals on which fish populations depend: these living systems are not ‘out there’, disconnected from humanity. On the contrary: our fates are intertwined. They are, in a real sense, us." (missing reference)

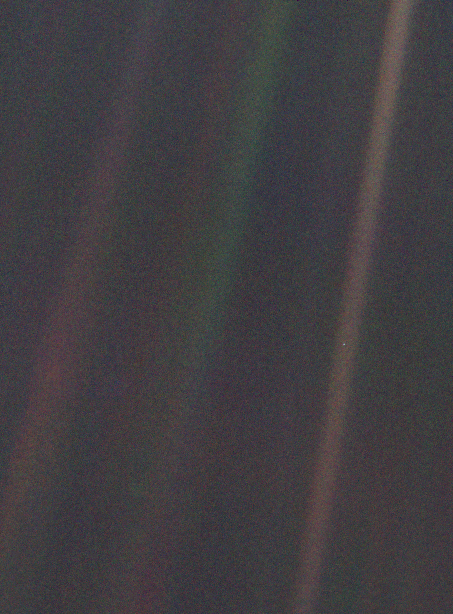

To conclude this reflection, I'd like to share the image Pale blue dot (figure 2), which I recommend contemplating with the monologue that accompanies it.

"Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us." (missing reference)

References

- MACBA Barcelona Oficial. (2019). "El estado sin tiempo: un presente sin pasado", a cargo de Daniel Inclán. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMy6Mk2spDg

- Garcés Mascareñas, M. (2017). Nova il·lustració radical. Editorial Anagrama.

- CCCB. (2016). "Inacabar el món", a càrrec de Marina Garcés. Retrieved from https://www.cccb.org/es/multimedia/videos/marina-garces/223347

- Adorno, T. W. (1976). Terminología filosófica. Taurus Ediciones.

- Servigne, P., & Stevens, R. (2021). Colapsología (M. Suárez Bravo, Trans.; Segunda edición).

- Arendt, H. El concepto de historia antiguo y moderno. In Entre pasado y futuro: ocho ejercicios sobre la reflexión política. (pp. 49–100). Península.

- Chakrabarty, D. (2009). The Climate of History: Four Theses. The University of Chicago Press, 35(2), 197–222. doi: 10.1086/596640

- Aleksievich, S. (2016). Entrevista de l’autora a si mateixa sobre la història silenciada i sobre per què Txernòbil posa en dubte la nostra visió del món. In La pregària de Txernòbil. Crònica del futur. 978-84-15539-92-6.

- CCCB. (2015). La condició humana en l’Antroposcè, a càrrec de Dipesh Chakrabarty. Retrieved from https://www.cccb.org/es/multimedia/videos/dipesh-chakrabarty/221059

- Marcuse, H. (1999). One-dimensional man: studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society (2. ed., reprint). London: Routledge.

- Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (2006). Dialéctica de la Ilustración: Fragmentos filosóficos (8. Aufl, Issue serie filosofia). Madrid: Trotta.

Footnotes

-

Do not misunderstand me with this analogy: at no point do I want to assert that the historical trajectory is deterministic. Nevertheless, it is a common thought among astrophysicists: one resolution to the Fermi Paradox (the statistical expectation of abundant intelligent life in the Universe contrasted with the fact that we haven't detected any) is the theory that the destiny of every intelligent civilization is self-extermination. And it's an interesting question. Are all civilizations doomed to implosion and collapse? ↩

-

I would like to emphasize that the word 'stock' in reference to sentient non-human individuals highlights the mechanism of reducing animals to biocapital and reveals the logic of domination through language. ↩